Why is the U.S. dragging its feet on resource coordination and a national shutdown? Could it be the U.S. is using its own citizens as guinea pigs to achieve ‘herd immunity?’

Trump handling of the current crisis may be the real disaster: Slow to issue test kits. Lack of effective leadership in coordinating a national response to the crisis. Knowing U.S. hospitals have inadequate equipment to handle an epidemic surge in infected patients, Trump has left it up to the individual states to institute lock-downs. Is the Trump’s Administration tepid response to this national crisis, itself, a pandemic strategy?

While countries around the world began to lock down workplaces, schools, and public gatherings in response to the rapidly spreading coronavirus, the United Kingdom’s initial strategy sent many into an uproar. At first, the U.K. chose not to shut down large gatherings or introduce stringent social distancing measures. In a plan that surprised many in the medical community, officials instead described a plan to suppress the virus through gradual restrictions, rather than trying to stamp it out entirely.

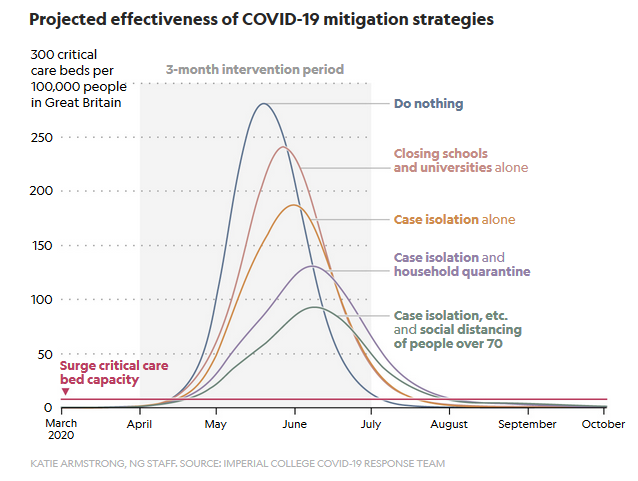

The strategy, an attempt to build “herd immunity,” involved allowing “enough of us who are going to get mild illness to become immune,” Sir Patrick Vallance, the U.K. government’s chief scientific adviser, told Sky News on March 13. If the risks of COVID-19 were not so high, it would technically be possible to bring about herd immunity by allowing the disease to run rampant through a population. However, evidence shows that scenario would lead to high rates of hospitalization and need for critical care, straining health service capacity past the breaking point.

After new simulations of the outbreak from Imperial College London showed how badly hospitals would be overwhelmed, the U.K. suddenly reversed course on Monday and introduced new social distancing measures. By Friday, the Prime Minister had ordered all pubs, restaurants, gyms, and cinemas to close. Still, the question of herd immunity’s role in slowing the coronavirus lingers because of how it might determine the success of vaccine development—and the chances that the virus may flare back up once social distancing policies end. Immune responses within a cell can take around 24 hours to trigger, says Elly Gaunt, a virologist at the University of Edinburgh’s Roslin Institute. A full-blown immune response can take another three days—which means that a respiratory virus like the flu, which can replicate in as little as eight hours, is way ahead of the game.

That’s why someone’s first experience with an infectious disease can be so nasty. The immune system is not so easily tricked a second time: When it’s beaten an invader once, it keeps a specialized weapons cache dedicated to that particular pathogen, ready to mount a high-speed reaction if it’s ever detected again. So, the second time the disease shows up in your body, the virus won’t have that handy head start. People with immunity are “duds for transmission,” says Katie Gostic, a University of Chicago researcher who studies immunity to influenza. And when viral transmission can’t sustain itself an epidemic will slow down and end, she explains.

Herd immunity can only be reached when a precise proportion of a community becomes resistant to an infectious disease, says Yonatan Grad, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. You can’t have just some herd immunity, he explains, in the same way you can’t be just a little bit pregnant. To have herd immunity, each infected person must, on average, infect less than one person (though clearly, it’s not possible to infect half a person; if some infected people pass on the infection and others don’t, the average transmission rate will be less than one.) Once the transmission rate drops below one, a community has herd immunity. That won’t stop each and every case, but it will prevent the disease from spreading indefinitely.

Research so far suggests that the coronavirus has a lower infection rate than measles, with each infected person passing it on to two or three new people, on average. This means that herd immunity should be achieved when around 60 percent of the population becomes immune to COVID-19. –National Geographic

Comments

Post a Comment